Structural reform

While progress in the area of structural reform has been modest, positive developments outweigh negative ones in most of the economies where the EBRD invests. Competitiveness scores have been revised upwards in multiple countries, driven by improvements in the business climate. Modest progress has also been observed in the area of good governance. Green scores have improved, with countries continuing to strengthen their commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. While financial inclusion has also improved, progress in respect of other areas of inclusion is lacking. Despite little change in financial resilience scores, marked progress has been seen in the area of energy resilience. Modest increases have also been observed in integration scores, driven by improvements in the quality of logistics services and related infrastructure.

Introduction

The EBRD has been tracking the progress of transition and structural reforms since the first Transition Report was published back in 1994. However, the methodology underlying that assessment has evolved over the years. A major change occurred last year, when the Transition Report 2017-18 unveiled a new set of indicators based on the EBRD’s revised concept of transition, which was developed in 2016.1

As explained in last year’s report, EBRD economists have developed a methodology which measures transition economies’ progress against six key qualities of a sustainable market economy, looking to see whether they are competitive, well-governed, green, inclusive, resilient and integrated. Each of the resulting “assessment of transition qualities” (ATQ) scores has a scale of 1 to 10 (where 1 is the worst and 10 is the best) and is based on a wide range of indicators.

The purpose of this section of the report is threefold. First, updated ATQ scores are presented for all of the economies where the EBRD invests, allowing us to see where each economy stands in relation to its neighbours and countries in other regions. Second, a comparison is drawn with last year’s scores, highlighting countries and sectors where significant developments have occurred. And third, for selected economies (based on the availability of data), an analysis of developments over a longer period (from 2010 to 2017) is also carried out.

Transition scores

While progress with structural reforms has been slow in many areas and many countries, positive developments outweigh negative ones overall (see Table S.1 and Chart S.1).2 It should be noted, in this regard, that the methodology has been refined further since last year’s report, and the new refined methodology has been applied to calculate scores for both 2017 and 2018. Therefore, scores for 2017 may differ from those published last year. One example of such a change is the addition of a knowledge economy index to the data used to assess economies’ competitiveness, as discussed below.3

Competitive

Over the last year, many countries have seen improvements – albeit very modest ones – in their competitiveness scores. Increases have been observed in several SEE and EEC countries (including Albania, Azerbaijan, Belarus, FYR Macedonia, Kosovo and Serbia), driven by further improvements in the business climate.

Well-governed

Improvements in the area of good governance have been concentrated primarily in the EEC region, with progress being observed in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Moldova and Ukraine. Increases in these countries’ scores have been driven by marginal improvements in the perceived quality of governance practices and standards in key areas, including the protection of private property and the availability of adequate frameworks for challenging regulations.

Green

Some improvements have been observed in green scores over the past year, especially in central Europe and the Baltic states (CEB) and the SEE and EEC regions. These have been driven primarily by changes in indicators measuring economies’ commitments and actions in respect of their preliminary plans for addressing greenhouse gas emissions and tackling climate change (termed “intended nationally determined contributions” or INDCs).

Inclusive

Modest progress has been seen across the three components of the inclusion index (youth, gender and regional inclusion) over the past year. Notable improvements have been observed in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Moldova, where percentages of women and young people with bank accounts have risen further, and improvements have also been seen in the perceived quality of education. In addition, women now account for a larger percentage of employers in Moldova. Several SEE countries have also seen some progress – albeit from a low base – in respect of financial aspects of youth and gender inclusion. In the Slovak Republic, meanwhile, a new law was adopted in early 2018 with a view to addressing regional disparities by incentivising investment in economically disadvantaged regions. At the same time, the country’s newly launched 10-year educational development programme aims to reduce skills mismatches in the labour market.

Resilient

This quality consists of two distinct components: financial resilience and energy resilience. These are discussed in turn below.

Financial resilience

Very little progress has been observed over the last year in indicators of financial resilience. A number of countries have seen modest declines in the dollarisation of the financial sector, while loan-loss provision coverage ratios have increased in several economies (including Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Ukraine). At the same time, the resilience of the financial sector remains weak in some countries, with further increases in NPL ratios being observed in Kazakhstan and Ukraine.

Energy resilience

The CEB, EEC and SEE regions have seen the most notable improvements in energy resilience over the past year. Thanks to its adoption of the Electricity Market Law in 2016 and the Regulator Law in 2016, Ukraine is now compliant with the EU’s Third Energy Package Directives, with a substantially improved legislative and regulatory framework governing the energy sector and a stronger role for the country’s energy regulator. Meanwhile, a number of changes to the gas sector have improved the overall investment climate in the industry across the value chain.

Integrated

Modest increases in integration scores have been observed in several countries over the last year, most notably in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kosovo, Montenegro and Romania. Those increases have been driven primarily by improvements in the quality of logistics services and infrastructure (particularly transport infrastructure), as well as further increases in net FDI and non-FDI capital inflows as a percentage of GDP. At the same time, integration scores have declined in some CEB countries, with the quality of logistics services (as measured by the World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index) deteriorating in Latvia, Lithuania and the Slovak Republic. A similar trend can be observed in Egypt, Jordan and Turkey. Some improvement – albeit from a relatively low base – can also be observed in the quality of logistics and related services in certain Central Asian countries.

A multi-year analysis

The assessments above are based on score changes over a very short period of time, so they tell us little about the underlying long-term trends. In order to explore such longer-term patterns, the analysis in this section focuses on developments in respect of selected economies and qualities over the period 2010-17, on the basis of available data.

Source: EBRD.

| Competitive | Well-governed | Green | Inclusive | Resilient | Integrated | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | 2018 | 2017 | |

| Central Europe and the Baltic states | ||||||||||||

| Croatia | 5.8 | 5.9 | 6.0 | 6.2 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 6.9 | 6.9 |

| Estonia | 7.7 | 7.7 | 8.3 | 8.4 | 6.7 | 6.7 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| Hungary | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 7.5 | 7.6 |

| Latvia | 6.6 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 7.5 |

| Lithuania | 6.4 | 6.4 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 7.4 | 7.4 | 7.2 | 7.5 |

| Poland | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 6.9 | 6.9 | 7.1 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 7.9 | 6.8 | 6.8 |

| Slovak Republic | 7.0 | 7.1 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.7 | 6.6 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.5 |

| Slovenia | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.6 | 6.7 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 8.0 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.3 |

| South-eastern Europe | ||||||||||||

| Albania | 5.0 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 5.7 | 5.7 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.3 |

| Bulgaria | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 6.4 | 6.2 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.9 | 6.8 |

| Cyprus | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 6.9 | 7.0 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 8.1 | 7.9 |

| FYR Macedonia | 5.7 | 5.6 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.0 |

| Greece | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.3 |

| Kosovo | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.7 |

| Montenegro | 5.2 | 5.2 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 6.2 |

| Romania | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 6.8 | 6.7 |

| Serbia | 5.3 | 5.1 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 6.2 |

| Turkey | 5.2 | 5.2 | 6.2 | 6.2 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 7.3 | 7.2 | 5.8 | 5.9 |

| Eastern Europe and the Caucasus | ||||||||||||

| Armenia | 4.5 | 4.5 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 6.1 | 6.2 | 6.0 | 5.8 |

| Azerbaijan | 3.7 | 3.6 | 5.8 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 3.9 | 6.0 | 5.9 |

| Belarus | 4.7 | 4.5 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 7.0 | 6.9 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 5.6 | 5.5 |

| Georgia | 4.5 | 4.5 | 6.3 | 6.4 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 6.0 | 5.8 | 6.4 | 6.3 |

| Moldova | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5.5 |

| Ukraine | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.6 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.9 |

| Russia | 5.2 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 6.3 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 5.4 |

| Central Asia | ||||||||||||

| Kazakhstan | 5.1 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.2 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 4.9 |

| Mongolia | 4.2 | 4.2 | 5.2 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 5.4 |

| Tajikistan | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 3.3 | 4.0 | 3.9 |

| Turkmenistan | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 4.4 | 4.3 |

| Uzbekistan | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.5 |

| Southern and eastern Mediterranean | ||||||||||||

| Egypt | 3.2 | 3.1 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 5.8 | 5.6 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| Jordan | 4.0 | 4.0 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 5.9 | 5.9 | 6.3 | 6.4 |

| Lebanon | 4.3 | 4.4 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| Morocco | 4.0 | 3.9 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 5.6 | 5.6 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| Tunisia | 3.9 | 3.9 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.7 |

| West Bank and Gaza | 2.5 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 3.8 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

SOURCE: EBRD.

NOTE: Scores range from 1 to 10, where 10 represents a synthetic frontier corresponding to the standards of a sustainable market economy. Scores for 2017 have been updated following methodological changes, so may differ from those published in the Transition Report 2017-18.

Source: EBRD.

BOX S.1. How sensitive are these quality scores to the choice of methodology?

Calculating composite indicators such as the ATQ scores involves multiple steps and a number of methodological choices. If different choices are made, the values that are calculated for these composite indicators may vary, and so may the resulting rankings for each economy. The issue of the quality of the underlying data and the difficulty of measuring the phenomena of interest (such as the quality of education) introduces further measurement errors.

Source: EBRD and authors’ calculations.

Note: The ranges shown indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles of the distributions of average scores across all six qualities. Calculations are based on 1,000 simulation runs.

Source: EBRD and authors’ calculations.

Note: The ranges shown indicate the 10th and 90th percentiles of the distributions of rankings, calculated based on average scores across all six qualities. Calculations are based on 1,000 simulation runs.

Methodological notes

Transition indicators: six qualities of a sustainable market economy

The transition indicators reflect the judgement of the EBRD’s Office of the Chief Economist and the Economics, Policy and Governance department on the transition progress in its countries of operations. According to this approach a sustainable market economy is characterised by six qualities: Competitive, Well-governed, Green, Inclusive, Resilient and Integrated.

Data preparation and treatment of missing observations

The underlying data for the majority of indicators either enter the composite index directly or are scaled using a meaningful related measure. A number of indicators may themselves be composite indices (for example, EBRD SME index or EBRD Knowledge Economy index) and they enter the ATQ composites in index form. No further transformation is applied to the underlying indicators before normalisation. For some indicators no data is available for the current year and simple imputation methods are used.2 One method of imputation uses the latest available observation from past years, thus assuming that no change from the latest available observation has been observed. When there are no past or present observations available for a particular indicator, then, based on the judgement of EBRD experts, either the regional mean (using the EBRD classification of regions for its countries of operations) or the observed regional minima are used to impute the missing observations.

For the regional disparity component of the Inclusive ATQ, imputations for the southern and eastern Mediterranean (SEMED) economies and Turkmenistan are necessary due to the LiTS (source of the data for this indicator) not being administered in these countries. In particular, a new series is generated for a full set of countries including SEMED and Turkmenistan based on available indicators on rural-urban disparities from other sources. Using the statistical relationship between the scores produced by this series and LiTS-based regional inclusions scores, missing SEMED and Turkmenistan values were imputed. Further details of this imputation are available on request.

To mitigate the effect that extreme values may have on scores, observations that lie above the 98th percentile are considered outliers and replaced by the next value within the acceptable range. Outlier detection and replacement is only applied to select continuous variables.

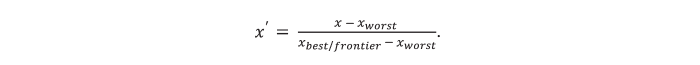

Normalisation

The raw data for each indicator are normalised to the same scale using the min-max normalisation method as follows:

The resulting scores are then rescaled from 1 to 10, where 10 represents the frontier for each quality. The frontier is taken to be the best performance, observed either in an EBRD country of operations, a comparator country or a theoretical value determined based on expert judgement.

If an observation for a country exceeds the selected frontier, then the normalised value of the indicator is capped at the frontier value. For indicators where any deviation from the frontier is undesirable, values either below or above the frontier are treated similarly (the same score is computed and assigned to two observations that are equally distant from the frontier).

Aggregation

Normalised indicators are aggregated to a single composite index (by quality) using weights determined by expert judgement (see Table M.1 for details of weights). A simple weighted averaging method is used for aggregation.

Changes to methodology from 2017

During the past year, further work on strengthening the methodology for computing ATQ indices was carried out. This work did not involve changes to the process of computation of ATQ indices and it focused largely on modifications to the set of underlying indicators. The primary purpose of this work has been ensuring that ATQs better capture the relevant phenomena and allow adequate monitoring of the pace of reforms and transformation in the region. This work resulted in the addition of new indicators, discontinuation of the use of others and use of equivalent data series from alternative sources. Details of these changes are provided below.

Competitive

- Indicators added to the quality composite: EBRD Knowledge Economy index and Global Value Chain (GVC) participation indicator

- Indicators removed from the quality composite: Global Innovation Index, number of broadband connections per population

- Changes to sources of data: import tariffs, share of services in total exports, labour productivity.

Well-governed

- For all BEEPS-based indicators, share of respondents with certain values is used as an indicator now instead of mean of responded values.

Green

- Indicators removed from the quality composite: Water pricing indicator.

Inclusive

- The gender equality component of the composite was revised and includes a different set of indicators this year

- The opportunities for youth component of the composite was also substantially revised. The component retained some of the indicators from last year (quality of education, PISA scores, hiring and firing flexibility index) and three new indicators were added

- The number of indicators entering the regional disparities component of the composite was reduced.

Resilient

- Treatment of deviations from frontier for a number of indicators changed.

Integrated

- Indicators added to the quality composite: Foreign direct investment restrictiveness indicator, losses and spoilages during transport, number of internet users, time required to get electricity

- Indicators removed from the quality composite: Investing across borders indicator

- Trade volume indicator now also includes services trade.

The following tables show, for each quality, the components used in each quality index along the indicators and data sources that were fed into the final assessments.

| COMPETITIVE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier country | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| Market structures [53%] | Applied tariff rates a (weighted average) [13%] | World Bank Development Indicators (WDI), International Trade Centre, Market Access Map (MACMAP), 2016 | Georgia | 0.66 | 9.35 | |

| Subsidies expense a (per cent of GDP) [13%] | IMF, Government Finance Statistics, 2016 | Albania | 0.12 | 7.05 | ||

| Doing Business (Distance to Frontier (DTF) Score) [13%] | World Bank Doing Business, 2017 | United States of America | 83.67 | 53.57 | ||

| DB Resolving insolvency score (DTF Score) [13%] | World Bank Doing Business, 2017 | Japan | 93.16 | 20.3 | ||

| Number of new entries d (per 1,000 people) [6%] | WDI, 2016 | Estonia | 20.76 | 0.15 | ||

| Starting a business d (DTF Score) [6%] | World Bank Doing Business, 2017 | Canada | 98.23 | 63.6 | ||

| SME Index adjusted (0 = worst, 1 = best) [13%] | EBRD, 2017 | United Kingdom | 0.69 | 0.32 | ||

| ISO 9001 certification/pop [13%] | ISO Institute, WDI, 2016 | Slovak Republic | 0.11 | 0 | ||

| Share of business services in service exports (per cent of total service exports) [13%] | WDI, 2016 | United Kingdom | 77.55 | 8.38 | ||

| Capacity to generate value added [47%] | Economic Complexity Index [14%] | Harvard Centre for International Development, 2016 | Japan | 2.26 | -1.38 | |

| Knowledge Economy Index (KEI) adjusted (1 = worst, 10 = best) [14%] | EBRD, 2017 | Sweden | 8.15 | 1.97 | ||

| WB Logistics Performance Index (1 = worst, 5 = best) [14%] | World Bank WDI, 2016 | Germany | 4.44 | 1.96 | ||

| WEF quality of education (1 = worst, 7 = best) [14%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United States of America* | 5.58 | 2.46 | ||

| Labour productivity (output per worker, GDP (constant 2011 int. US$ PPP)) [14%] | ILO, 2017 | United States of America | 111,056 | 7,544 | ||

| Credit to private sector b (per cent of GDP) [14%] | WDI, 2016 | Canada* | 100 | 10.94 | ||

| Global value chain participation [14%] | EORA UNCTAD, 2017 | Slovak Republic | 0.81 | 0.33 | ||

| WELL-GOVERNED | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier country | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| National level governance [60%] | Quality of public governance [33%] | Regulatory quality (-2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [14%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2016 | Sweden | 1.85 | -2.09 |

| Government effectiveness (-2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [14%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2016 | Japan | 1.83 | -1.14 | ||

| Transparency of government policy making (1 = worst, 7 = best) [14%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | Canada | 5.67 | 2.71 | ||

| Private property protection e (1 = worst, 7 = best) [7%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United Kingdom | 6.3 | 2.87 | ||

| IP rights protection e (1 = worst, 7 = best) [7%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United Kingdom | 6.09 | 2.93 | ||

| Regulatory burden (1 = worst, 7 = best) [14%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | Germany | 4.77 | 1.88 | ||

| Political instability a (4 = major obstacle, 0 = no obstacle) [14%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS V, 2012 | Azerbaijan | 0 | 0.96 | ||

| Freedom of media a, f (100 = least free, 0 = most free) [7%] | Freedom House, 2016 | Sweden | 11 | 98 | ||

| Freedom of media a,f (100 = least free, 0 = most free) [7%] | Reporters Without Borders, 2017 | Sweden | 12.33 | 84.19 | ||

| Integrity and control of corruption [33%] | Control of corruption g (-2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [19%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2016 | Sweden | 2.22 | -1.46 | |

| Perception of corruption g (0 = highly corrupt, 100 = not corrupt) [19%] | Transparency International, 2017 | Sweden | 84 | 19 | ||

| Perception of corruption g (4 = major obstacle, 0 = no obstacle) [19%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS V, 2012 | Estonia | 0.01 | 0.71 | ||

| Informality a (4 = major obstacle, 0 = no obstacle) [22%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS V, 2012 | Jordan | 0.04 | 0.62 | ||

| Implementation of anti-money laundering/counter-terrorism-financing (CFT)/tax exchange standards a (0 = low risk, 10 = high risk) [22%] | International Centre for Asset Recovery, 2017 | Lithuania | 3.67 | 8.28 | ||

| Rule of law [33%] | Judicial independence (1 = worst, 7 = best) [20%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United Kingdom | 6.35 | 1.99 | |

| Enforcement of contracts h (1 = worst, 7 = best) [10%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 5.69 | 2.06 | ||

| Efficient framework for challenging regulations (1 = worst, 7 = best) [20%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 5.21 | 2.06 | ||

| Enforcement of contracts h (DTF Score) [10%] | World Bank Doing Business, 2017 | Sweden | 94.61 | 42.75 | ||

| Rule of law (-2.5 = worst, 2.5 = best) [20%] | World Bank Governance Indicators, 2016 | Sweden | 2.04 | -1.56 | ||

| Effectiveness of courts a (4 = major obstacle, 0 = no obstacle) [20%] | World Bank/EBRD BEEPS V, 2012 | Jordan | 0 | 0.28 | ||

| Corporate level governance [40%] | Corporate governance frameworks and practices [80%] | Structure and functioning of the board (0 = worst, 5 = best) [20%] | EBRD Legal Transition Team Corporate Governance Assessment, 2016 | Czech Republic* | 3.68 | 1.78 |

| Transparency and disclosure i (0 = worst, 5 = best) [10%] | EBRD Legal Transition Team Corporate Governance Assessment, 2016 | Czech Republic* | 4.66 | 1.96 | ||

| Internal control (0 = worst, 5 = best) [20%] | EBRD Legal Transition Team Corporate Governance Assessment, 2016 | Czech Republic* | 4 | 0.6 | ||

| Rights of shareholders j (0 = worst, 5 = best) [10%] | EBRD Legal Transition Team Corporate Governance Assessment, 2016 | Czech Republic* | 4.2 | 2.75 | ||

| Stakeholders and institutions (0 = worst, 5 = best) [20%] | EBRD Legal Transition Team Corporate Governance Assessment, 2016 | Czech Republic* | 4.16 | 0.18 | ||

| Transparency and disclosure i (1 = worst, 7 = best) [10%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | Canada | 6.22 | 3.33 | ||

| Rights of shareholders j (DTF Score) [10%] | World Bank Doing Business, 2017 | Canada* | 78.33 | 38.33 | ||

| Integrity and other governance-related business standards and practices [20%] | Ethical behaviour of firms (1 = worst, 7 = best) [100%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | Sweden | 5.98 | 2.65 | |

| GREEN | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier country | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| Physical Indicators [37%] | Climate change mitigation [35%] | Electricity production from renewable sources, including hydroelectric (per cent of total) [17%] | WDI, 2014 | Albania | 100 | 0.36 |

| Value added in industry per unit of CO2 emissions (GVA(US$) /total CO2) [17%] | World Bank, International Energy Agency (IEA), 2015 | Sweden | 15,646 | 473.37 | ||

| MWh consumed per unit of CO2 emissions from electricity and heat generation (MWh/total CO2) [17%] | World Bank, IEA, 2015 | Albania* | 42.88 | 0.12 | ||

| GDP per unit of CO2 emissions from residential buildings from fuel combustion (GDP(US$)/total CO2) [17%] | World Bank, IEA, 2015 | Sweden | 2,346,478 | 7,335 | ||

| CO2 emissions from transport a (number of registered vehicles/total CO2) [17%] | IEA, WHO, 2012 | Tajikistan | 0.79 | 7.38 | ||

| Agricultural GVA per unit of GHG emissions (GVA (US$)/total CO2eq) [17%] | FAO, World Bank, 2016 | Japan | 2,909 | 53.34 | ||

| Climate change adaptation [35%] | NDGAIN human habitat score a [25%] | Notre Dame Global Adaptation Index (NDGAIN), 2016 | Germany | 0.25 | 0.64 | |

| Aqueduct water stress index a [25%] | Aqueduct, World Resources Institute, 2013 | Slovenia | 0.83 | 3.14 | ||

| NDGAIN projected change in cereal yield a [25%] | NDGAIN, 2016 | United Kingdom* | 0 | 0.85 | ||

| WDI Occurrence of droughts, floods, extreme temperatures a (per cent of population exposed 1990-2009) [25%] | World Bank WDI, 2009 | Sweden* | 0 | 5.38 | ||

| Other environmental areas [30%] | Population weighted mean annual exposure to PM2.5a [25%] | World Bank WDI, 2016 | Sweden | 5.2 | 126.03 | |

| Waste intensive consumption a (kg municipal solid waste/household expenditure (US$)) [25%] | Waste Atlas, 2015 | Japan | 0.01 | 0.33 | ||

| Waste generation per capita a (kg / population) [25%] | Waste Atlas, 2015 | Armenia | 118.9 | 777 | ||

| Number of animal (terrestrial and marine) species threatened (per cent of total number assessed)a [13%] | The IUCN red list of threatened species, 2017 | Estonia | 0.04 | 0.18 | ||

| Number of plant (terrestrial and marine) species threatened (per cent of total number assessed) a [13%] | The IUCN red list of threatened species, 2017 | Estonia* | 0 | 0.27 | ||

| Structural Indicators [63%] | Climate change mitigation [36%] | Market support mechanism index (0=no support, 0.5 regulatory support, 1=revenue support) [25%] | IEA, 2015 | Canada* | 1 | 0.5 |

| INDC rating (0 = no INDC, 0.5 = INDC but not ratified, 1 = ratified INDC) [25%] | World Resource Institute, 2017 | Japan* | 1 | 0 | ||

| Carbon price (0 = worst, 1 = best ) [25%] | World Bank International Carbon Action Partnership (ICAP), 2017 | France* | 1 | 0 | ||

| Fossil fuel subsidies a (per cent of GDP) [25%] | IMF, 2015 | Sweden* | 0 | 11.91 | ||

| Climate change adaptation [26%] | NDGAIN agricultural capacity a [20%] | NDGAIN, 2016 | Japan | 0.36 | 0.99 | |

| World Governance Indicators: Institutional Quality [40%] | WDI, 2016 | Sweden | 1.82 | -1.62 | ||

| Adaptation mentioned in INDCs (1 = yes, 0 = no) [40%] | CGIAR, 2017 | Armenia* | 1 | 0 | ||

| Other environmental areas [30%] | Vehicle emission standards (0 = worst, 6 = best) [34%] | United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2015 | Canada* | 6 | 0 | |

| Municipal waste collection coverage (per cent of total) [34%] | Waste Atlas, 2015 | Germany* | 100 | 39 | ||

| Proportion of terrestrial protected area 1990/2014 (per cent of total area) [16%] | World Bank, 2016 | Slovenia | 53.64 | 0 | ||

| Proportion of territorial seas protected (per cent of total area) [16%] | World Bank, 2016 | Slovenia | 100 | 0 | ||

| Cross-cutting [8%] | Number of environmental technology patents (per GDP (billion US$)) [100%] | OECD, World Bank, 2014 | Japan | 0.61 | 0 | |

| INCLUSIVE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier country | Frontier Value | Worst performance |

| Gender equality [33%] | Social Institutions and Gender Index a, b (0 = best) [20%] | OECD, 2014 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 0 | 0.43 | |

| Difference between women’s and men’s labour force participation rate a, c [20%] | ILOSTAT Database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 0 | 0.79 | ||

| Share of women in managerial employment c (per cent of total in managerial employment) [20%] | ILOSTAT Database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 50 | 7.1 | ||

| Share of women employers c (per cent of total employers) [20%] | ILOSTAT Database, 2017 | Moldova | 50 | 3.85 | ||

| Share of women with bank accounts (per cent of total women) [20%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | Sweden | 100 | 0.79 | ||

| Opportunities for youth [33%] | Percentage of young people with bank accounts (15-24) (per cent of total youth population) [17%] | World Bank Financial Inclusion Database, 2017 | Canada* | 100 | 0 | |

| Hiring and firing flexibility [17%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United States of America | 5.44 | 2.37 | ||

| PISA test score performance in three fields (reading, math and science) [17%] | PISA, OECD, 2015 | Estonia | 524 | 362 | ||

| Perception of quality of education system (1 = worst, 7 = best) [17%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United States of America | 5.62 | 2.14 | ||

| Median age [17%] | UN-DESA, World Population Prospects, 2015 | Japan | 46.35 | 19.34 | ||

| Difference between youth (15-24) and adult (25+) unemployment rates a, b [17%] | ILO, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 0 | 29.6 | ||

| Regional disparities [33%] | Percentage of establishments with checking or savings account a [13%] | EBRD, BEEPS V and MENA, 2012-14 | Russia | 0 | 0.45 | |

| Quality of administrative, health and education systems a [13%] | EBRD, LiTS, 2016 | Estonia | 0.07 | 0.87 | ||

| Access to water a [13%] | EBRD, LiTS, 2016 | Germany* | 0 | 0.97 | ||

| Access to heating a [13%] | EBRD, LiTS, 2016 | Cyprus | 0 | 0.99 | ||

| Access to computer a [13%] | EBRD, LiTS, 2016 | Germany | 0.25 | 0.79 | ||

| Access to internet a [13%] | EBRD, LiTS, 2016 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 0.26 | 0.86 | ||

| Household head labour market status a (worked in the last 12 months) [13%] | EBRD, LiTS, 2016 | Czech Republic | 0.39 | 0.71 | ||

| Completed education of the household head in working age (25-65)a [13%] | EBRD, LiTS, 2016 | Uzbekistan | 1.25 | 3.05 | ||

| RESILIENT | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier country | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| Energy sector resilience [30%] | Liberalisation and market liquidity [50%] | Sector restructuring, corporatisation and unbundling (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [33%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Germany* | 0.67 | 0 |

| Fostering private sector participation (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [33%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | United States of America* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| Tariff reform (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [33%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| System connectivity [20%] | Domestic connectivity (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [35%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0.09 | |

| Inter-country connectivity (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [65%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Germany* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| Regulation and legal framework [30%] | Development of an adequate legal framework (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [50%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0 | |

| Establishment of an empowered independent energy regulator (0 = worst, 0.67 = best) [50%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 0.67 | 0 | ||

| Financial stability [70%] | Banking sector health and intermediation [65%] | Capital adequacy ratio [6%] | IMF Financial Soundness Indicators (FSI), IHS Markit, National Authorities, 2017 | Moldova | 0.31 | 0.06 |

| Return on assets [6%] | IMF FSI, IHS Markit, National Authorities , IMF Article IV, Fitch – Sovereign Data Comparator, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2017 | Georgia | 3.12 | -12.47 | ||

| Loan-to-deposits ratio c [6%] | IMF FSI, IHS Markit, National Authorities, IMF Article IV, Fitch – Sovereign Data Comparator, EBRD FI Risk Reports, latest available | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 1 | 0.36 | ||

| Non-performing loans (NPLs) to total gross loans a (per cent of total gross loans) [6%] | IMF FSI, IHS Markit, National Authorities, IMF Article IV, Fitch – Sovereign Data Comparator, S&P BICRA, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2017 | Canada | 0.59 | 54.54 | ||

| Loan loss reserves to NPLs ratio b (provisions to NPLs) [6%] | IMF FSI, IHS Markit, National Authorities, EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2017 | FYR Macedonia* | 100 | 16.67 | ||

| Asset share of five largest banks a [6%] | WB Global Financial Development Database (GFDD), IMF Financial System Stability Assessment (FSSA), EBRD FI Risk Reports, 2015 | United States of America | 46.53 | 99.89 | ||

| Asset share of private banks [6%] | WB GFDD/EBRD FI Risk Reports, IMF Article IV, IMF FSSA, Bank Focus, latest available | Sweden* | 100 | 0 | ||

| Assets to GDP c (per cent of GDP) [6%] | IMF FSI, EBRD, Internal Sovereign Risk Report, Bank Focus, National Authorities, IHS Markit, latest available | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 100 | 36.48 | ||

| Credit to private sector c (Per cent of GDP) [6%] | WB GFDD, S&P BICRA, IMF Article IV, WDI, 2016 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 80 | 4.02 | ||

| Foreign currency loans a (per cent of total loans) [6%] | IMF FSI, IMF Article IV, IHS Markit, National Authorities, 2017 | United States of America* | 0 | 100 | ||

| Liquid assets (per cent of short-term liabilities) [6%] | IMF FSI, WB GFDD, IMF Article IV, National Authorities, EBRD FI Risk Overview, 2017 | Russia | 167.38 | 15.54 | ||

| Alternative sources of funding [12%] | Other Financial Corporation (OFC)’s assets b (per cent of GDP) [6%] | IMF FSI, WB GFDD, IMF Article IV, National Authorities, EBRD FI Risk Overview, IMF FSSA, AFDB, latest available | Canada* | 100 | 0.32 | |

| Stock market capitalisation b (Per cent of GDP) [6%] | WB, Lithuanian National statistics and Stock Exchange (CEIC), IMF FSSA, IMF FSI, WDI, 2015 | France* | 79.24 | 0 | ||

| Regulation, governance and safety nets [24%] | Well-functioning deposit insurance (1 = No, 5 = Partially, 10 = Yes) [6%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | United Kingdom* | 10 | 1 | |

| Bank risk management capacity and corporate governance (1 = No, 5 = Partially, 10 = Yes) [6%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 10 | 1 | ||

| Adequate legal and regulatory framework (1 = No, 5 = Partially, 10 = Yes) [6%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Germany* | 10 | 1 | ||

| Independent supervisory body (1 = No, 5 = Partially, 10 = Yes) [6%] | EBRD assessment, 2017 | Czech Republic* | 10 | 1 | ||

| INTEGRATED | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Sub-components | Indicators | Source | Frontier country | Frontier value | Worst performance |

| External integration [50%] | Trade openness [33%] | Total trade volume (Perc cent of GDP) [50%] | World Bank WDI, 2017 | Slovak Republic | 182.59 | 28.71 |

| Number of regional trade agreements (RTAs) [17%] | WTO, 2017 | France* | 41 | 1 | ||

| Binding overhang ratio a, b (%) [17%] | WTO, 2016 | Sweden* | 0 | 46.3 | ||

| Number of non-tariff measures a [17%] | WTO, 2017 | Azerbaijan | 2 | 4,493 | ||

| Investment openness [33%] | Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows (per cent of GDP) [50%] | IMF International Investment Position Statistics, 2017 | Cyprus | 14.89 | -0.84 | |

| Number of bilateral investment agreements [25%] | UNCTAD, 2017 | Germany | 185 | 8 | ||

| FDI Restrictions indicator a [25%] | OECD, 2017 | Slovenia* | 0.01 | 0.24 | ||

| Portfolio openness [33%] | Non-FDI inflows (per cent of GDP) [50%] | IMF International Investment Position Statistics, 2017 | Cyprus | 9.48 | -5.46 | |

| Chinn-Ito indicator [50%] | Chinn-Ito, 2015 | Sweden* | 2.37 | -1.9 | ||

| Internal integration [50%] | Domestic transport [25%] | Quality of infrastructure: Roads (1 = worst, 7 = best) [13%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | Japan | 6.11 | 2.41 |

| Quality of infrastructure: Railroads (1 = worst, 7 = best) [13%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | Japan | 6.58 | 1.03 | ||

| Quality of infrastructure: Ports (1 = worst, 7 = best) [13%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United States of America | 5.7 | 1.3 | ||

| Quality of infrastructure: Air transport (1 = worst, 7 = best) [13%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | United States of America | 6 | 2.6 | ||

| LPI: Logistics competence (1 = worst, 5 = best) [13%] | WB Logistics Performance Index (LPI) database, 2017 | Germany | 4.28 | 1.96 | ||

| LPI: Tracking and tracing (1 = worst, 5 = best) [13%] | WB LPI database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 4.27 | 1.84 | ||

| LPI: Timeliness (1 = worst, 5 = best) [13%] | WB LPI database, 2017 | No economy was at the frontier in 2018 | 4.45 | 2.04 | ||

| Proportion of products lost to breakage or spoilage during shipping a [13%] | WB Enterprise Surveys, 2013 | Latvia* | 0 | 4.3 | ||

| Cross-border transport [25%] | LPI: Customs, Infrastructure, International shipments (1 = worst, 5 = best) [50%] | WB LPI database, 2017 | Germany | 4.11 | 1.95 | |

| Cost of trading across borders (DTF Score) [50%] | WB Doing Business, 2017 | France* | 100 | 42.23 | ||

| Energy [25%] | Quality of electricity supply (1 = worst, 7 = best) [50%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2017 | France | 6.76 | 1.65 | |

| Losses due to electrical outages a [25%] | WB Enterprise Surveys, 2013 | Estonia | 0.1 | 10.1 | ||

| Time required to get electricity a (days) [25%] | WDI, 2017 | Germany | 28 | 281 | ||

| ICT [25%] | Broadband access [25%] | WEF Global Competitiveness Index, 2016 | France | 42.74 | 0.07 | |

| Internet users [25%] | ITU, 2016 | United Kingdom | 94.78 | 17.99 | ||

| Level of competition for internet services (50 = Monopoly, 75 = Partially competitive, 100 = Competitive) [50%] | World Bank The Little Data Book, 2017 | United Kingdom* | 100 | 50 | ||

* Additional countries are at the frontier. Further information is available on request

a Inverted before normalisation

b Capped at frontier

c Mirrored from frontier

d Mean of “New business entries” and “Starting a business” indicators enters the final index

e Mean of “Private property protection” and “IP rights protection” indicators enters the final index

f Mean of “Freedom of media” indicators enters the final index

g Mean of “Control of corruption” and “Perception of corruption” indicators enters the final index

h Mean of “Enforcement of contracts” indicators enters the final index

i Mean of “Transparency and disclosure” indicators enters the final index

j Mean of “Rights of shareholders” indicators enters the final index

Subscribe to the EBRD Transition Report 2018-19 mailing list.

Sign up to receive important announcements and emails about the Transition Report.